Principle 6

Consider diverse teaching and learning frameworks and methods

Teaching is both an art and a science. Inclusive pedagogies acknowledge that all teaching and learning occur within a social and political context and embrace the significance of the context and the environment on student and instructor experiences within the learning environment. Inclusive teaching is developed as a practice over time, as instructors regularly reflect on their teaching and student learning and make changes as needed.

There are a host of empirically informed and theoretical frameworks and methods drawn from the field of education as well as the social sciences, the professions, STEM fields, the humanities, and interdisciplinary fields, all of which can inform the practice of teaching. Many of these frameworks can support educators who are committed to excellence in teaching, which includes the practice of inclusive teaching.

Inclusive Teaching and Learning Frameworks

Inclusive teaching frameworks are the why (theoretical perspective and approaches) and how (methods and strategies) of the teaching experience that inform and guide the what (course goals and content) and who (students and instructor/learning community). Learning and considering diverse and inclusive frameworks and approaches to course development and delivery are essential first steps toward teaching excellence. The when is thus the intentional work of planning in order to teach inclusively.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to inclusive teaching and learning. Instead, inclusive instructors consider a host of flexible, research-informed frameworks and methods. Utilizing one or more of these frameworks will allow instructors to theoretically, empirically, and inclusively ground their teaching practices well before entering the classroom, lab, or studio.

Trauma-informed framework for college classrooms

Trauma-informed teaching, like inclusive teaching, assumes there are contextual factors that have the potential to inform and inspire but also derail students from learning. An inclusive educator works to mitigate the latter reality.51 Thus, trauma-informed teaching does not entail doting or providing therapy, but instead acknowledges how trauma affects learning environments. The US Department of Health and Human Services has identified specific trauma-informed principles, including safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; and empowerment.52 Mays Imad, an expert in trauma-informed teaching, explained that experiencing identity-based marginalization can be stressful on the brain. Therefore, instructors who utilize trauma-informed practices pay attention to cultural, historical, and gender issues.53 Harris and Fallot offer a framework of core values for trauma-informed educators to use in tandem with a host of other inclusive teaching and learning approaches, frameworks, and pedagogies, as noted in Table 1.54 For the first core value of “safety,” this framework also aids instructors in identifying campus resources and support beyond the learning environment so that educators can think about how to support student success in their courses outside the classroom. Trauma-informed teaching can be a starting point for inclusive pedagogy. All members of a university community, including instructors, need to work collaboratively with a shared commitment for the safety of their students.

Table 1: Core Values of Trauma-Informed Teaching and Practice

(Source: Adapted from Harris & Fallot, 2001)

| Core values | Questions to guide the development of trauma-informed practices |

|---|---|

| Safety (physical and emotional) |

How safe is the building or environment? Are sidewalks and parking areas well lit? Are there easily accessible exits? Are directions clear and readily available? Are signs and other visual materials welcoming, clear, and legible? Are restrooms easily accessible (e.g., well marked and gender inclusive)? Are first contacts or introductions welcoming, respectful, and engaging? |

| Trustworthiness |

Do students receive clear explanations and information about tasks and procedures? Are specific goals and objectives clear? How does the program handle challenges between role clarity and personal and professional boundaries? Choice and control? Are instructors informing each student about the available choices and options? Do students get a clear and appropriate message about their rights and responsibilities? Are there negative consequences for making particular choices? Are these necessary or arbitrary consequences? Do students have choices about attending various class sessions? Do students choose how contact is made (e.g., by phone or by mail to their home or other address)? |

| Empowerment |

How do educators recognize each student’s strengths and skills? Do educators communicate a sense of realistic optimism about students’ capacity to achieve their goals? How can educators focus on skill development or enhancement for each class, contact, or service? |

Backward design

Backward design is a straightforward, adaptable, and foundational framework that helps align course learning goals, activities, and assessments.55 This framework starts by inviting the instructor to focus on the ultimate goal—increasing knowledge and competencies. Ask yourself what you want your students in this course to be able to know, do, or value, instead of asking yourself what content you want to cover in this course this term. Backward design is well supported by learning theory and has been shown to increase desired learning outcomes. Backward design invites course instructors to slow the course development process in the beginning stages and to intentionally consider the methods, course content, strategies, and, most importantly, their students. This intentional approach to course development can help instructors to communicate course expectations (refer to Principle 2) and enhance learning for all students.

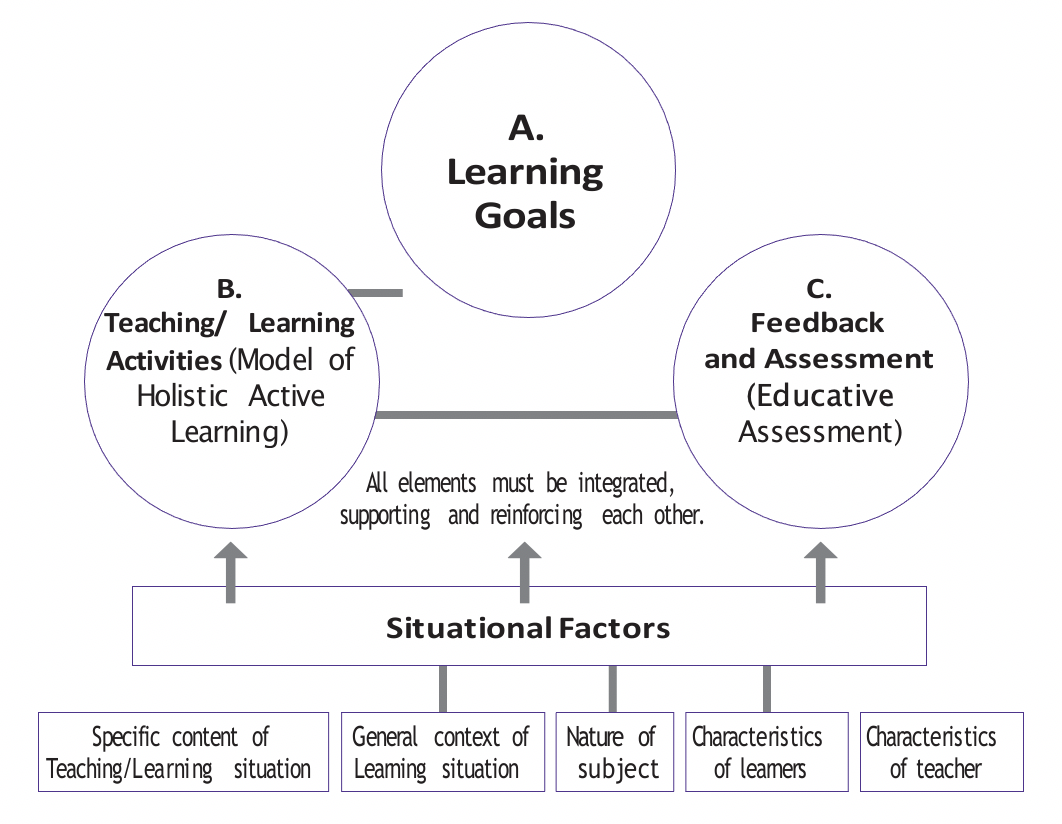

Chart 1: Key Components of Integrated Course Design

(Source: Fink, 2013)

Integrated course design

Integrated course design expands backward design in a way that is specific to teaching and learning in higher education.56 The methodology shifts away from the static stages of backward design to offer a continuous planning strategy informed by environmental and contextual factors that may affect student learning. This inclusive framework entails an expanded process that assumes the learning environment influences the course content delivery and therefore invites instructors to consider those factors when planning teaching and assessment. The factors include the characteristics of the learners and the teacher, the nature of the subject, and the general and specific context of the learning situation. This framework can be particularly useful to instructors reflecting on their own and students’ social identities, cultivating an inclusive course climate, and considering varied assessments.

5Es

The 5E model was initially developed by the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS).57 It has been widely used in the sciences, but the model’s five-step approach (engagement, exploration, explanation, elaboration, and evaluation) is useful for all instructors as they develop individual class sessions. This model is considered an inclusive approach because the instructor operates from the premise that all students enter into the learning environment with curiosity and capacity. The 5E model is grounded in constructivist theory, which suggests that students learn best when they have opportunities to experience and interact with new phenomena and reflect upon their own learning. Many college instructors do this intuitively when they use the first few minutes of their classes to engage students with a content-based “ice breaker” activity that allows students to explore, experiment, and apply their prior knowledge and understanding. The instructor might then design the lesson of the day around elaboration by scaffolding or bridging the new learning they are aiming for, so that students gain a better capacity to articulate their deepened understanding. Ideally, the class session would finish with the instructor providing opportunities for students to engage in self-assessments of their learning as well as engaging their own assessment of students’ learning during the session.

Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) was developed as a model to address diverse learning needs of students in the classroom. It invites educators to not simply react to a student who requires specialized support but instead to plan a learning experience with the assumption that all students enrolled have a diversity of learning needs and interests. This approach is less concerned with students’ abilities and identities but rather with the instructors’ inclusive approach to improve the learning environments for all students. It incorporates diverse strategies and learning processes that engage students who have a variety of learning preferences.58 The model can be applied across an entire course or used for a single class or unit. Northwestern instructors can learn more about applying UDL to course design through an open educational resource and by connecting with AccessibleNU.

Advanced/Transformative Frameworks, Methods and Pedagogies

Once instructors are actively and regularly engaged in their own learning and self-exploration concerning social and institutional inequities and have begun intentionally incorporating introductory inclusive frameworks and methods into their coursework, they may consider more advanced inclusive pedagogies. Transformative pedagogies that are informed by critical race theory, feminist theory, disability studies, decolonizing pedagogies, pedagogy of the oppressed, and queer theory are social-justice-oriented interventions that have advanced the aforementioned inclusive teaching and learning frameworks and methods. These transformative frameworks and methods often have a greater emphasis on incorporating course content that critiques systems of social and economic power and resists all forms of oppression and domination. They emphasize an intentional development of educational spaces that are safe, inclusive, and liberatory, and they work to ensure that marginalized and minoritized people are valued within the classroom and in society.59 Students’ emotional expression is acknowledged in the classroom, and personal experience is viewed as a valid and valued form of knowing and meaning making.60 Advanced inclusive educators craft and embrace a learning environment where instructors and students teach and learn from one another and knowledge is coconstructed.61 They tend to embrace community building, collaboration, dialogue, and coalition building over competition.62 They unite theory and action with goals of praxis and social transformation.63 Collectively, these frameworks expand upon the foundations of inclusive teaching to conceptualize the teaching and learning environment as a critical site for advancing social justice within and beyond the classroom.

Teaching Strategies

Instructors can implement one or more of the above frameworks in their teaching.

Faculty Excellence in Inclusive Teaching

“When I think of inclusive teaching and how it’s played out in my courses, I have found that the approaches I’ve used to create inclusive learning environments have been to the benefit of all the students in my classroom. Bringing my own experience and identity into the classroom, for example, has had a profound effect in how students see me not only as the source of content and grades but as an approachable human being they can seek out for guidance and even mentorship. That’s especially important for those from underrepresented or marginalized communities, but I’ve seen the positive outcomes stemming from that principle with all my students. Communicating clear course standards and expectations, a good practice in normal times, has been even more vital during the pandemic and remote learning. The guidelines provide a framework that has made it easier for me to map out and visualize what I’m doing in my teaching and what needs more work. It’s a continual process of learning and refining.”

Marcelo Vinces

Weinberg College Adviser; Assistant Professor of Instruction, Molecular Biosciences